RAGNAR KJARTANSSON: Guilt Trip

The Paradox of Ragnar Kjartansson

“… haunting isn’t it? I love the theme of shame and remorse. It is life’s secret invisible thread. Like our good old Mr. Ingmar Bergman and Mr. Woody Allen have also put it so well in their movies.” – R.K.

People who have been involved with acting are likely to know The Paradox of the Actor. In this 18th century text, Denis Diderot deals with the conflicting nature of performance, that to appear real, the actor must be artificial; in order to move the audience, the most brilliant actor must himself remain unmoved – he does not feel anything onstage. Many have rejected his argument and this detached acting style, the most prominent opposition originating in the 19th century with Konstantin Stanislavski’s search for “theatrical truth.” His approach was later developed into method acting (dominant today in Hollywood films and much of Western theater), in which actors draw on their own emotions, memories, and experiences to influence their portrayals of characters. However, Diderot’s question remains unresolved; how we can speak of truth in performance, which of its very nature is a lie?

Ragnar Kjartansson was born into a family of actors and has lived the paradox of the actor. Although not pursuing the profession, he has dedicated his artistic career to explore acting; it is the backbone to most of his work. Throughout his cultural activities he has foregrounded performance and positioned it beyond any clear distinction from real life. Consequently, faced with questions of truth and deception, he has with much rigor embraced feelings of guilt and remorse.

As a student in the Icelandic Academy of the Arts, Kjartansson made a video with his mother, the actress Gudrún Ásmundsdóttir. He has since repeated this same enterprise with the aim to do so regularly in the future. Me and My Mother (2000 – ongoing) starts with the two of them in a domestic setting, facing forward and looking seriously into the camera. Suddenly the mother turns to her son and spits in his face, then faces the camera again. His only reaction is to close his eyes as the spit hits him and glance at his mother before turning back to the original position. She now gathers spit in her mouth and launches it at him again. This is repeated throughout the video until his face and clothes are drenched.

Kjartansson puts Ásmundsdóttir to the test, as a well-known performer and as a mother, casting her in a vulnerable role that blurs the line between performance and life. He manipulates the situation as to deprive her of the viewer’s sympathy, giving way for psychoanalytic interpretation. “That’s what it’s like to be raised by an actor!” Passively he accepts what the viewer might interpret as guilt-wrapped outbursts of a person who lives a life conflicted by truth and fiction. At the same time he dares her professionally. She is removed from her sheltered, professional frame, (a narrative on stage or a movie screen), in her home where her son directs her to express the opposite of motherly love. Nevertheless, she takes on the challenge and delivers a remarkable tragicomic performance. Lars von Trier’s film, The Five Obstructions, comes to mind –

the director putting his favorite filmmaker, Jørgen Leth, in the position of redirecting his best film (according to von Trier), confronted with different, whimsical obstructions of his admirer. Kjartansson and von Trier echo the Oedipal trajectory; they demonstrate sincere admiration and love for their mentors as well as an urge to destroy them.

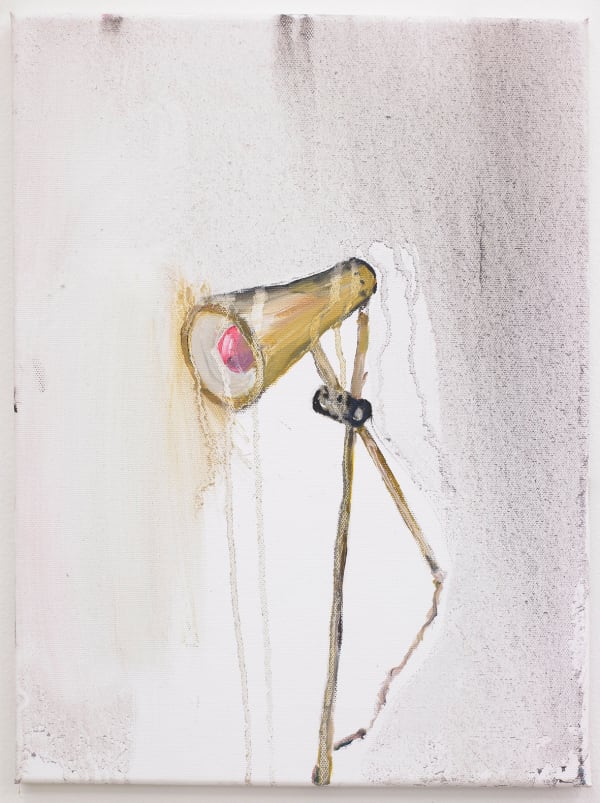

This time around, in Guilt Trip (2007), Kjartansson works with Laddi, a comedian, who has been present throughout the lives of the generation of Icelanders of which the artist is part. He has invented countless characters, performing on television, radio, in theater, film and on music albums. The entire nation has most likely at some point been at the verge of wetting themselves with laughter when Laddi has slipped into one of his roles. Then there is the paradox; no one seems to know the actor. Behind multiple identities of extreme personas and a support layer of the artistic alias “Laddi” resides the person, Thorhallur Sigurdsson. He is a reclusive man, so known for his shyness that the media long ago gave up trying to interview him. To the public he is a tabula rasa – one day he is opening a bar, the next he is selling holiday homes in Spain. This performer, who has been adamant in separating his art and personal life, is now seen in Ragnar Kjartansson’s video, hiking in the wilderness with a rifle and a bag of bullets. There is no wig, no makeup, no character and – perhaps most surprisingly – no comic relief. Occasionally he fires his weapon aimlessly before heading on and shooting again. It is clear that Kjartansson has scripted this and directed, he did not document an everyday act of this person. Around the video he has constructed a painted environment, suggesting the bare winter landscape that the man is walking through. Here and there are painterly strokes of distant explosions mirroring the gunshots. Other paintings are variations on a theme of conflicted expression, props or extras blurting out emotions in a stage set for the performance in the video. Rather than the video being an extension of the painting installation, however, they derive from it, for at the center of the work is the indistinct identity of the gunman.

Guilt Trip in a way is a tribute to Laddi. It would not have been conceived with any other actor. Kjartasson highlights the paradox of the actor by choosing a person, who is only known as a multitude of identities. The work respects his anonymity without suggesting any of his previous, well-known characters. It sets him in a situation free from the pressure of acting a role; the physical undertaking of the hike and the expressive gesture of firing the gun consume all attention. What is the guilt? One is tempted to interpret the gun as a substitute for his professional effort. Much like the hunter, the comedian relies on the right time and the right place for success. Paradoxically Laddi is in the middle of nowhere aiming coincidentally at nothing – he might as well be shooting blanks. Has he wasted his life entertaining an unknown audience? Has he lost himself on the way? Are the targets for his bullets the numerous identities that he has put out there? Yet again, Kjartansson has thwarted the clear distinction between art and life, contesting the truth in performance, the very nature of which is a lie.

“The guilt is a light shining on me. My heart molten as wax. Punch me in the stomach on a cold summer day or leave me in the moor, smoking a cigarillo.” – R.K.

-Markús Thór Andrésson